Relay anomalies

Tor relays provide a wealth of information about themselves when joining the network. Some of that is necessary in order to make them participate as relays, think of the IP address and ORPort they are running on or the exit policy they picked, in case the relays are exit nodes. Other information is optional and can even be faked: think of relay nicknames, operator contact information or observed bandwidth valies.

Regardless of which particular information about relays we look at, be it self-reported or measured, it's prone to anomalies. The same goes for relay behavior. At first glance that seems to be counterintuitive as we know the Tor source code (assuming the operator did not mess with that) and have a lot of experience how relays ramp up and behave while running. However, there are a number of things that, in reality, interfere at this point: there might be bugs in the source code we overlooked or plain configuration errors/experiments done by the operator. Finally, usually not all the underlying infrastructure needed for running relays is in the operator's control but might influence together with network affects what particular operators experience (and we see in our data) when running relays.1

Uptimes and restarts

As Winter et al.2 write (on p.6):

For convenience, Sybil operators are likely to administer their relays simultaneously, i.e., update, configure, and reboot them all at the same time. This is reflected in their relays’ uptime.

Being a Sybil3 operator means running relays that seem to belong to different entities while they are in fact being run by the same person or group.

Given the observation about operator behavior quoted above, Winter et al. propose an uptime matrix, which

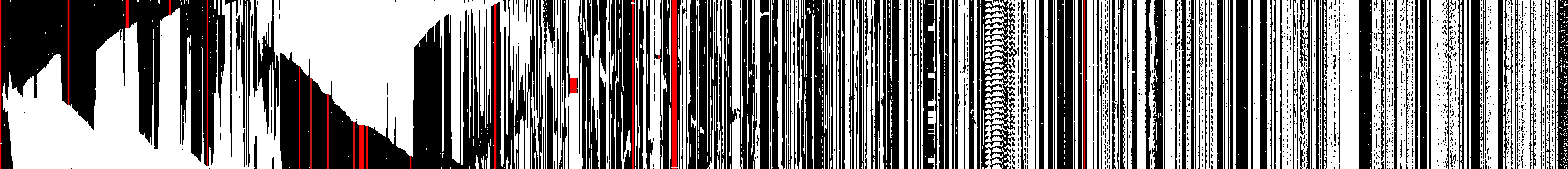

consists of the uptime patterns of all Tor relays, which we represent as binary sequences. Each hour, when a new consensus is published, we add a new data point—“online” or “offline”—to each Tor relay’s sequence. We visualize all sequences in a bitmap whose rows represent consensuses and whose columns represent relays. Each pixel denotes the uptime status of a particular relay at a particular hour. Black pixels mean that the relay was online and white pixels mean that the relay was offline.

This is how it for example looks like for June 2016:

The interesting clusters of relays with identical uptime (5 relays at a minimum) are marked in red.

Nearest-neighbor ranking

Identical uptimes are not the only indicator for Sybil relays. Winter et al. propose another technique using the Levenshtein distance4 to quantify the similarity between two relays (p. 7):

Our algorithm turns the router statuses and descriptors of two relays into strings and determines their Levenshtein distance.

As Winter et al. noted, representing relays as strings and thereby ignoring for instance the topological proximity of IP addresses (p.15) points to significant room for improvement of the algorithm. Sui et. al.5 pick this up in a follow-up paper. They consider the following relay attributes with the respective algorithms:

| Relay attribute | Algorithm |

|---|---|

| nickname | improved Levenshtein distance |

| hostname | Jaro-Winkler similarity |

| IPv4 address | Hamming distance |

| exit policy | Jaccard similarity |

| uptime | custom6 |

| ipv4 port | data-equivalence-based approach/inverse document frequency |

| country | data-equivalence-based approach/inverse document frequency |

| as number | data-equivalence-based approach/inverse document frequency |

| version | data-equivalence-based approach/inverse document frequency |

| platform | data-equivalence-based approach/inverse document frequency |

The relay similarity score is then computed out of the similarity scores of the 10 relay attributes (p.296):

node_similarity_scores(a,b) = nickname_score ∗ 0.2 + hostname_score ∗ 0.1 + uptime_score ∗ 0.05 + exitpolicy_score ∗ 0.1 + country_score ∗ 0.05 + asnum_score ∗ 0.1 + ipv4add_score ∗ 0.1 + ipv4port_score ∗ 0.1 + version_score ∗ 0.1 + platform_score ∗ 0.1

Traffic manipulation, shaping and sniffing

When a user sends a request over a Tor circuit to a destination the assumption is that this request travels to/from the respective Tor relay IP addresses over the Tor circuit before reaching the destination and a response is getting relayed through the network back to the user similarly, both without any interference and traffic logging by parties in between. Any case that deviates from this pattern can be seen as an anomaly. 7 summarize findings both from past studies and their own research where traffic tampering or sniffing happened between the exit node and the request's destination. They encountered and documented cases of misconfiguration (DNS resolution issues, antivirus tools interfering with Tor traffic), MitM attacks (e.g. against HTTP/HTTPS traffic) and traffic snooping (stealing of FTP and IMAP credentials). 8 9

Relay bandwidth history and overload

XXX: bw faking, read/write gaps in history, overload

Implementation status

Both Winter et al.'s uptime and nearest-neightbor ranking tools are implemented

in margot10.

Monthly output of the uptime matrix is available on Gitlab pages11.

For the nearest-neighbor ranking, there is the caveat that we have a slightly

different version of it deployed, compared to what got developed in

Winter et al.'s paper, as arti, which margot is using under the hood,

doesn't have support for server descriptors available yet12.

Thus, while Sybilhunter13 computes the Levenshtein distance based

on:

| relay attribute | source |

|---|---|

| Nickname | consensus |

| OR address | consensus |

| ORPort | consensus |

| DirPort | consensus |

| Flags | consensus |

| Tor version | consensus |

| PortList | network status |

| Bandwidth average | server descriptor |

| Bandwidth burst | server descriptor |

| Operating system | server descriptor |

| Published | server descriptor |

| Uptime | server descriptor |

| Contact | server descriptor |

margot resorts to:

| relay attribute | source |

|---|---|

| Nickname | consensus |

| OR address | consensus |

| Flags | consensus |

| Tor version | consensus |

| Weight | consensus |

for now.

-

There are many examples we could bring up at this point. A particular good one is operators being (differently) affected by a large relay operator restarting their relays at a different autonomous system, see: https://gitlab.torproject.org/tpo/network-health/analysis/-/issues/105. ↩

-

Winter, Philipp et al.: Identifying and characterizing Sybils in the Tor network. In: Proceedings of the 25th Usenix Security Symposium, 2016. ↩

-

Douceur, John R.: The Sybil Attack. In: Proceedings of Peer-to-Peer Systems, 2002. ↩

-

Levenshtein, Vladimir Iosifovich: Binary Codes Capable of Correcting Deletions, Insertions, and Reversals. In: Soviet Physics-Doklady 10.8, 1966. ↩

-

Sui, J., Guo, W., Shi, X., Zhang, S., Hu, H.: Refining Node Similarity Analysis: An Optimized Nearest-neighbor Ranking Algorithm. In: IEEE 2nd International Conference on Control, Electronics and Computer Technology (ICCEC), 2024, pp.292-297. ↩

-

The authors count all the uptime values and divide the available range into 10 intervals. If the uptime difference of a relay compared to the reference relay is 0 then it gets a score of 1. If the target relay would be in the second interval (in the paper within [0,33749]) it would get a score of 0.9. Per slice further away from the reference relay the score of the target relay is reduced by 0.1 (see: p.295 for more details). ↩

-

Winter, Philipp et al.: Spoiled Onions: Exposing Malicious Tor Exit Relays. In: Proceedings of the 14th Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium (PETS), 2014. ↩

-

Zhang, Qingfeng et al.: ExitSniffer: Towards Comprehensive Security Analysis of Anomalous Binding Relationship of Exit Router. In: W. Lu et al. (Eds.): CNCERT 2021, CCIS 1506, pp. 93–109, 2022. ↩

-

Zhang, Qingfeng et al.: A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Impact on Tor Network Anonymity Caused by ShadowRelay. In: IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), 2023, pp. 1369–1375. ↩

-

https://tpo.pages.torproject.net/network-health/online_relays ↩